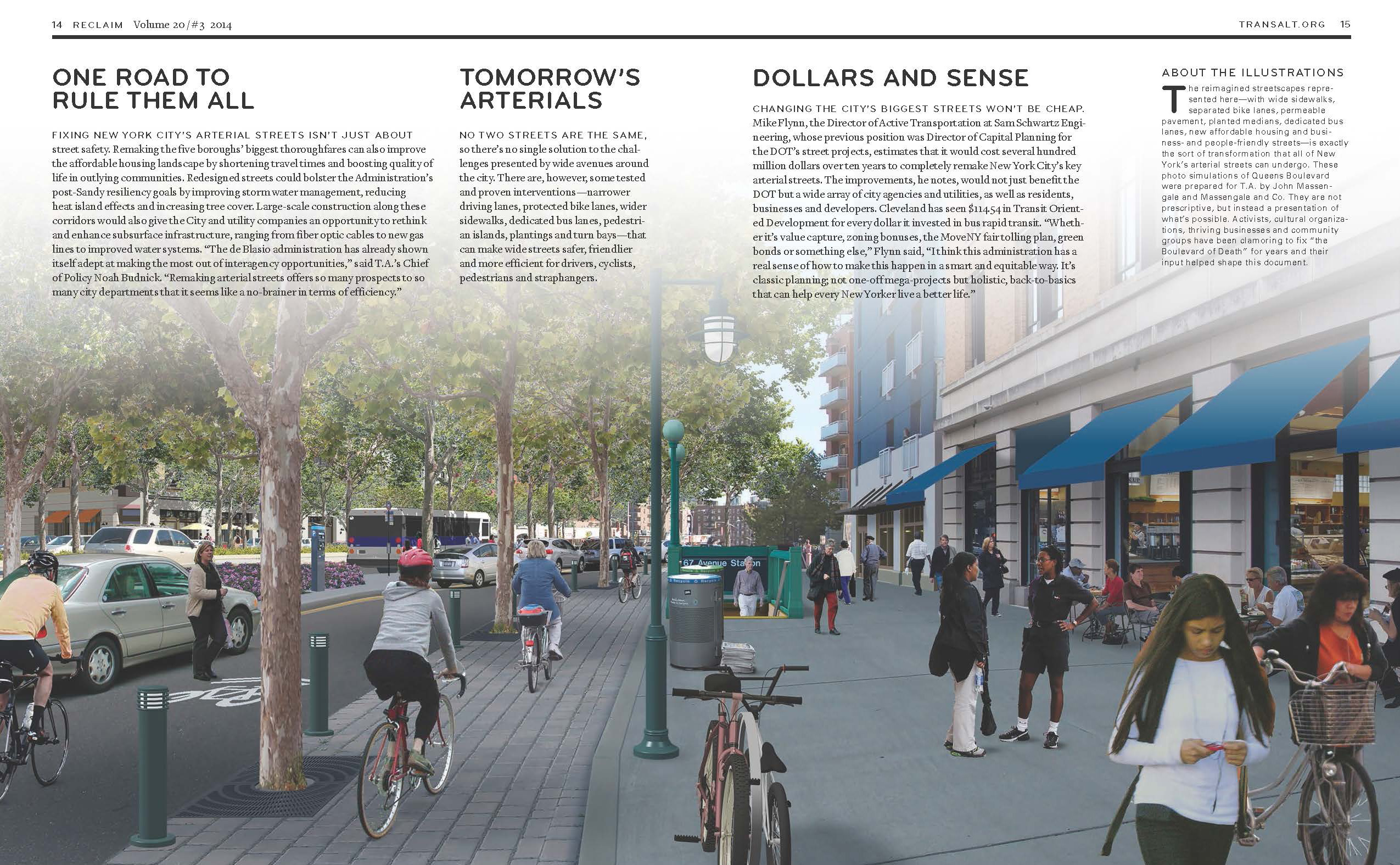

Queens Boulevard, Queens, New York. Before & After, looking southeast from 67th Road.

Massengale & Co LLC and Urban Advantage for Transportation Alternatives

Click on any of the images to see a larger version

More photos here

QUEENS BOULEVARD is one of the most dangerous streets in New York City. Sixty percent of the traffic fatalities in New York happen on ten percent of the streets, and Queens Boulevard is one of the two or three most dangerous of those. But it’s also the central artery of Queens, with five subway lines that run underneath it and a number of bus lines that run along it or across it, and in some stretches the Long Island Railroad is nearby. With a new 25 mile per hour speed limit and New York City’s new Vision Zero policies, Queens Boulevard is in a position to become dramatically different—and it may become one of the best places for the DeBlasio administration’s to zone for some of the affordable housing it wants to see.

You can see in the “Before” photo above that the market has clearly said over the years that housing away from the artery (even just half a block away) is more desirable for most than being right on the boulevard. Even the main shopping is one block away from the boulevard in some locations. The most obvious reasons for that are the 12 lanes of parking and traffic, with lots of pavement and few trees. But in Europe, “multi-way boulevards” (boulevards with separate side lanes like the ones on Queens Boulevard) are some of the great streets in the great cities, like the Champs Elysées and the Avenue Montaigne in Paris, or the Gran Via or the Avinguda Diagonal in Barcelona.

What makes those wide, heavily trafficked streets different from Queens Boulevard? Two of the most important differences are the grand allées of majestic street trees and the fact that the side lanes in Europe are designed to be places where pedestrians want to be. Compared to the European streets, Queens Boulevard is barren, and the cars on the wide side lanes go as fast as the cars in the center. Plus, even though there usually aren’t a lot of pedestrians on Queens Boulevard, the sidewalks can be so narrow that they become congested.

The two After images, made for the advocacy group Transportation Alternatives, began with visions of streets and wider sidewalks. The wider sidewalks make the side lanes narrower, so that they become slow lanes where cars have to share the space with cyclists and pedestrians. Next to the traffic lanes are protected bicycle planes, planted with permeable pavement which makes the trees part of a natural stormwater management system at the same time that it gives the roots room to grow.

The result is that more than 60 feet on each side of the boulevard becomes a place where pedestrians are comfortable. Coming out of the subways, they could stay on Queens Boulevard, and their greater numbers and the wider sidewalks would create a place for stores, restaurants, and cafés to flourish. Above those stores and restaurants could be new apartments, in tall buildings appropriately sized for the unusually wide street. And crossing the street would be much easier than it is today, because the heavy traffic volume would be limited to the six center lanes. Those lanes will have a new 25 mile per hour speed limit, and with this plan they would also have a wider, planted median, much like the one on Park Avenue, in Manhattan. Building sites that have been handicapped for more than three-quarters of a century would suddenly be unusual and desirable, with great access to the subway and to a beautiful and lively boulevard at the front door.

Queens Boulevard, Queens, New York. Before & After, looking southeast from 67th Road.

Queens Boulevard, Queens, New York. Before & After, looking southeast from 67th Road.

Massengale & Co LLC and Urban Advantage for Transportation Alternatives

From Reclaim (click on the images for larger versions):

Download the images in a small PDF

Download Reclaim at Transportation Alternatives

Larger images at photos.massengale.com

PS: In response to an email about these images, I wrote:

The images do not reflect the standard DOT approach of focusing primarily on the intersections. Traffic engineers do that because the intersections are where traffic flow is interrupted and traffic comes into conflict, with itself and with pedestrians and cyclists. Instead, the vision begin with making places where people want to be, and that naturally changes the emphasis to the space between the intersections. Jan Gehl rightfully says that city life takes place in the space between the buildings. And those buildings are between the intersections.

The most successful national retailers don’t allow fancy paving and streetscape “improvements” in front of their stores, because they want people looking at their storefronts instead of at the pavement or the benches. Similarly, a wholistic design for the public focuses on the space between the buildings rather than on the intersections. The designs by engineers and specialists that focus attention on the intersections weaken the public realm for everyone on foot.

Making streets where pedestrians and cyclists are comfortable naturally leads to streets where cars are going more slowly, and that leads to less conflict at the intersections. Implicit in the images is the idea that stop signs would replace stop lights in many places along the edges, and that there would be a greater lack of signs altogether. The center lanes would still have traffic lights, but cars in the side lanes would frequently come to complete stops at all times. Also part of the design is that on the edges, the parking lanes would be 7 feet wide, which is narrow, and the traffic lanes would be either 9 or even 8 feet wide, which is also narrow. That also causes drivers to go slowly, like the bollards that protect the trees. The trees, all traditional street trees such as Sycamores and London Planes, would be planted with Silva Cells below permeable pavement (creating a natural stormwater management system, as well as a healthier environment for the trees).

Traffic on the center lanes would flow as well as it does today, but more slowly, because slower is safer. Pedestrians now have to cross 8 wide lanes of fast-flowing traffic and 2 wide parking lanes, which is difficult to do during the sixty-second light cycle. If the traffic in the side lanes goes very slowly, however, the crossing is effectively reduced to the 6 center lanes, with a wide, planted median at the center. Crossing Queens Boulevard would be easier, safer, and more pleasant.

Affordable Housing & The Boulevard of Death Followup

QB Redux: I think that I shall never see…