Both divide the city. One brings traffic that creates an “asthma belt.”

Both divide the city. One brings traffic that creates an “asthma belt.”

A friend and colleague turned me onto AI obituaries. Think of them as interesting and amusing rather than morbid or morose. This one is from AI Copilot.

John Massengale AIA CNU Celebrating a Visionary Mind in Urban Design and Architecture

It is with both profound sorrow and deep admiration that we commemorate the life of John Massengale, an international thought leader whose career redefined the ways urban spaces can be both functional and inspiring. Known for his transformative insights into architecture, placemaking, and the intrinsic connections between design and community life, John dedicated his formidable talents to creating environments that spoke to the very soul of civic living.

From his early professional days, John was captivated by the notion that our streets, buildings, and public spaces are more than mere structures—they are vital canvases where history, culture, and innovation converge. He championed the idea that urban design is a dynamic dialogue between aesthetics and function, a perspective that propelled him to become a key figure in debates on sustainability, walkability, and the human experience. His passion resonated not only in his architectural solutions but also in his enduring commitment to nurturing communities with spaces that encouraged interaction and civic pride.

John’s scholarly contributions defined a generation of urban planners and architects. As co-author—with Victor Dover, FAICP—of the seminal work Street Design: The Secret to Great Cities and Towns, he provided an articulate analysis of how thoughtful street planning could reshape urban life. Earlier, his collaboration with renowned architect Robert A. M. Stern on New York 1900: Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism 1890–1915 cemented his reputation as a historian of urban form, delving into a period when innovative ideas began redefining American cities. These texts stand as enduring resources for anyone committed to understanding the fabric of our cities and how design influences our daily lives.

I haven’t read Beyond Architecture: The New New York yet.1 I will. For the moment I wanted to record some notes.

References

Paul Goldberger, “The Limits of Urban Growth,” New York Times, November 14, 1982, https://www.nytimes.com/1982/11/14/magazine/the-limits-of-urban-growth.html.

But if there is anything that the city’s current building boom, one of the largest in its history, has proved, it is that there are limits to density

Fred Bernstein, “Glazing Over Manhattan: Too many glass buildings, and the city becomes just another shiny office park,” Architectural Record, May 9, 2013, https://www.fredbernstein.com/display.php?i=276.

John Massengale,”A Short Discussion of Residential Building Heights in New York City,” There Are Two Types of Architecture, March 23, 2023, https://blog.massengale.com/2023/03/23/nycresheight/.

John Massengale,”A Short Discussion of Residential Building Heights in New York City,” There Are Two Types of Architecture, March 23, 2023, https://blog.massengale.com/2023/03/23/qandq/.

Reviews:

Michael Kimmelman, “How Can We Save the Best Parts of Our Cities?,” Critics Notebook, New York Times, November 30, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/30/arts/design/preservation-cities-new-york-intangible-heritage.html.

Benjamin Schneider, “New York City’s Historic Preservation Movement Is Having a Midlife Crisis,” CityLab Perspective, Bloomberg, December 19, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-12-19/nyc-historic-preservation-faces-crossroads-amid-new-housing-push.

Almost forty years ago, I owned a small house in the Greenwich “backcountry” just a few miles from the Westchester County Airport. One morning, I was talking on the phone with a friend whom I would see later in the day at an event he had organized in Miami. I was one of the speakers.

“Don’t you have to be at the airport?” he asked after a while.

I was very late, but luckily, this was before 9/11, and one could be on the plane within 10 minutes of arriving at the airport. And the roads between my house and the airport were sparsely settled.

I drove at ridiculous speeds along little winding roads. I was rushing down a narrow, twisting street on a steep hill when I saw a house out of the corner of my eye. “What was that?” I said to myself, out loud. “Someone evil lives there.” Continue reading

FIFTY-ONE YEARS AGO, the Pennsylvania Railroad tragically tore down Pennsylvania Station. Not only is it the best building ever torn down in New York, but in the combined Penn Station and Madison Square Garden, we got the worst building in New York.

Today, the railroads, Mayor Adams, and Governor Hochul want to tear down the block to my right. The Governor represents the Real Estate State: they believe the biggest donors get to build the biggest buildings. Like Vornado and the Related Companies. Mayor Adams represents the City of Yes, which has 4,000 pages of zoning changes that say “yes” to Big Real Estate.

If you want to see what the new block will look like, just walk over to Hudson Yards, the poster child for the City of Yes. New York City taxpayers spent over $5 billion to help Steve Ross — or maybe Stephen Roth, I get them mixed up — build that pile of unsustainable glass towers that make you feel like you’re in Dubai, Mumbai, or Shanghai. Dubai-on-Hudson, they call it. Whatever you call it, it’s not New York.

These things matter. “We shape our buildings; thereafter, they shape us,” Winston Churchill famously said. It’s the most quoted line in architecture because it’s true. Neuroscientists, psychologists, and sociologists confirm this. Architecture matters.

Cities and the buildings and streets and squares that make them are among the greatest achievements of humanity. We want to pass them on to our descendants. We don’t want to pass on inhumanly-scaled, energy-hog glass towers that increase climate change and make the world worse now and in the future.

New Yorkers love New York City. Our city needs buildings like the one on this block, Music Street. The block houses hundreds of residents and thousands of workers. New Yorkers like Eugene Sinigliano and Steve Marshall live and work and work here. So I close with a quote I got from today’s organizer John Mudd. It’s my new favorite quote.

“The question of what kind of city we want cannot be divorced from the question of what kind of people we want to be, what kinds of social relations we seek, what relations to nature we cherish, what style of life we desire, or what aesthetic values we hold.” – David Harvey, Rebel Cities.

CLICK HERE to open in Apple Podcasts

MUCK RACK automatically creates lists of articles written by individuals (like me). To this I’ve added some articles about me, and reviews of books I’ve written.

WHEN I was in graduate school, I was one of the editors of VIA IV: “Culture and the Social Vision.” I helped Robert A.M. Stern write New York 1900, Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism 1890-1915. My summer job turned into a five-year journey.

It turned out that Bob thought it would be good, and a good test, for me to write the first draft of the article from notes he had made and source material his Columbia students had collected over the years in a New York housing seminar he taught.

It’s a short history of the New York apartment house, with a particular focus on duplex apartments and the courtyard building. Here’s a scan of the article.

NOTE: The following was written for the Tenth Anniversary Edition of Street Design, The Secret To Great Cities and Towns, where it will appear in a shorter version. This version still needs some editing for its new context. A related essay from Street Design is “Location, Location, Location: Affordable Housing and Urban Form in Manhattan.”

THE SUBJECT OF HEIGHT LIMITS is relevant in any discussion of street design and urban design. While discussing East 70th Street, let’s briefly look at the planning regulations and building laws that contributed to the design of “the most beautiful block in New York.” The towers of the New York City skyline are world famous, but few stop to think that the tall towers were mainly office buildings. Until the 19th century, practicality limited buildings of all types to six or seven stories, because climbing to the top of taller buildings was too difficult as an everyday activity. By the 1870s, increasing use of safety elevators and steel-frame construction[1]* meant that new office buildings could be as tall as eight to ten stories. New Yorkers began to worry about the effect that tall residential buildings might have in residential neighborhoods.

Common law traditions suggested that homeowners had a right to the sunlight that would “naturally” reach their land.[2] Many residents of New York feared the shadows from tall buildings: in the 1880s they commissioned studies of “the high building question” and asked the city and the state to impose a moratorium on tall buildings. The New York State Legislature responded in 1885 with a bill limiting the heights of residential buildings in New York to 70 feet on side streets and narrow streets and 80 feet on avenues and wide streets.[3]

Interestingly, 70 feet was the same number ancient Rome used in the year 64 AD,[4] while Georges-Eugène Haussmann set lower height limits in Paris in 1859. Haussmannian boulevards 20 meters wide were lined with grand apartment houses 20 meters tall (65 ½ feet). Buildings on narrower streets were limited to 57 ½ feet.

A series of Tenement House Acts, building laws, and fire laws regulated the design and construction of residential buildings with multiple dwellings after 1867. With the rise of new technology and safety elevators, New York City raised residential building heights to 1½ times the street width or 150 feet, whichever was less (as mentioned above in “Height & Density: Quality & Quantity”). But not until thirty-one years after New York first limited the height of residential buildings, did the city famously pass America’s first zoning in 1916, similarly regulating non-residential buildings. Continue reading

NOTE: The following was written for the Tenth Anniversary Edition of Street Design, The Secret To Great Cities and Towns, where it will appear in a shorter version. This version still needs a little editing for its new context. Part 2 is another essay “A Short Discussion of Residential Building Heights in New York City.”

Since we wrote the first edition of Street Design, frequent discussions about building heights and population density have become common across America. Affordable housing for all is an important issue in many places, and there is a large and well-funded YIMBY movement that argues all zoning and height limits are restrictive regulations that make it more difficult and expensive to build. If cities, towns, and suburbs would just let developers build what they want, where they want—the YIMBY argument says—we would have all the affordable housing we need. The authors of Street Design think the truth is more complicated and nuanced. Here is a brief discussion of some of the reasons why we think that, and how the topic is closely related to street design.

In the original discussion of East 70th Street, we wrote that for thousands of years, good traditional streets frequently had a width-to-height ratio of 1 to 1 or 1 to 1½ (page TKTK). We did not say that for many years New York City limited residential building heights to 1½ times the width of the street (see “A Short Discussion of Residential Building Heights in New York,” page TKTK). The physical character of the great residential neighborhoods like the Upper East Side and Harlem come from that time and those limits. Today, the tallest “supertall” apartment tower on the new Billionaires’ Row in midtown Manhattan is 15.5 times as high as Fifty-Seventh Street is wide (and 25.8 times as tall as the with of 58th Street, on the north side of the building). The residential tower is also 300 feet taller than the Empire State Building, which was the tallest building in the world from the time it was built in 1931 until the first World Trade Center tower passed it in 1971. But New Yorkers never wanted to live in the Empire State Building or the World Trade Center. We talk about some of the reasons for that in the discussion of residential building heights in New York (page TKTK).

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs discusses “the kind of problem” that building and maintaining a healthy city is, calling it “a problem in handling organized complexity.”[EN29] Among the many interrelated issues, a successful business district with tall office towers has a different character than a neighborhood where people want to live. The YIMBY discussion, on the other hand, uses simplified talking points that emphasize one simple numeric quantity at a time: either building height, population density, the number of new building permits, or the residential unit count. Focusing on individual numbers one at a time erodes the quality of cities and city life. Paraphrasing what Jacobs said about looking at street traffic in terms of pedestrians versus cars (page TKTK, reducing building design to simply height or unit count is “to go about the problem from the wrong end.”[TKTK change EN30] Urbanists must be generalists, balancing social, economic, environmental, transportation, and health issues with urban form and placemaking. If not, specialists like traffic engineers and luxury housing developers can erode cities and their quality of life.

Density can be reduced to a number, but that number does not tell us what a place is like. East 70th Street is a part of the Upper East Side of Manhattan, which has over 100,000 people per square mile. That makes it one of the three or four densest residential neighborhoods in the Western world, more than twice as dense as the average neighborhood in Paris. Builders achieved that density 100 years ago with an average building height under 100 feet tall, and without an apartment building taller than 150 feet (see “A Short Discussion of Residential Building Heights in Manhattan,” pages TKTK). And as we have seen, there are other qualities that make some blocks better than others with almost identical dimensions.

Questions about urban form are essential for street designers. The height of the buildings on East 70th Street affects what the space between the buildings feels like, how the buildings enclose the street, and how they meet the street. The qualities that make East 70th Street feel good are missing in the photo of New Brooklyn (Figure 1.27), ironically on a street in the part of the borough widely known as Brownstone Brooklyn. The neighborhoods surrounding this section of Flatbush Avenue have the greatest collection of rowhouse streets in America: they create neighborhoods that are in great demand. [Figure 1.28]. Jane Jacobs was right when she observed that a greater variety of residential building types could have made the neighborhoods even better (page TKTK), but these new apartment towers don’t do that. Figure 1.27 shows what New Urbanists call “density without urbanism.”

TKTK NOTES

TKTK Add to EN30?

DELETED:

Location, Location, Location

Real estate developers and investors agree that the three most important factors in determining the value of a property or building are “location, location, and location.” Logically, the real estate market in Manhattan, Kansas is very different than the market on Manhattan Island. Yet YIMBYs argue that the reason so many cannot afford a good place to live is the same everywhere, regardless of location: we don’t have enough housing (which is true), and if we would just get out of the way of the market, it would provide housing for all. Let’s look at some of the reasons why we disagree with the second part of the argument.

First, why should we expect the market to provide affordable housing for all? Developers are not required to be philanthropists or altruists. They are business people, in business to make money. They respond to the local market. They typically look for the highest profits, which in most of America today means luxury housing, whether that means mansions, McMansions in the suburbs developed by production builders, or super-luxury “supertalls” like Billionaires’ Row in Manhattan.[EN31] Building low-income housing produces lower profits, or no profit, so few developers build that. And despite the “filter” or “trickle down” argument, no matter how many large, expensive condominiums New York City developers build as an investment vehicle for the global 1%, the supply will not trickle down to lower the rent on apartments for the poor.[EN32] For a variety of reasons, including the growing problem of income inequality, relying on the market to meet the needs of all has damaged our cities and towns with simplistic solutions that ignore the kind of problem a city is.

Location, location, location means that different markets have different conditions, different problems, and different solutions. Where is housing cheap? Where is land cheap? Where can buyers “drive till they qualify”? Not in New York or Los Angeles, and don’t forget the high cost of owning and operating cars.[EN33] Where is the economy strong, providing good jobs? Where do buyers want to live? (The COVID pandemic changed some of that.) What about income inequality? Where can a developer build houses or apartments that the average local buyer can afford, and will there be enough profit at that location? Are the global 1% or the global 5% driving up prices? Are hedge funds buying up all the starter homes? That’s a real thing.[EN34] Simply removing zoning will not solve the problem, although that probably is part of the solution in many places in America, which is primarily zoned for single-family houses in unwalkable sprawl. There is no question that we need more housing. The question is how to get housing that 80% of Americans can afford.

Some of those questions do not directly involve street design. But in the future, most affordable housing will be built in walkable cities and towns. Owning and operating a car is expensive (not to mention bad for the planet). The Center for Neighborhood Technology’s Housing and Affordability Index underlines just how expensive that is with data that shows combined housing and transportation costs. “Expensive” cities where one can live without owning a car frequently have lower overall combined costs for housing and transportation than regions that require lots of driving, particularly for households in which multiple family members must each own a car.[EN35] Without exception, every place that has low ownership rates for cars either has streets where people want to walk or has high rates of poverty, with people living there because it’s the best they can afford. The second condition is not “affordable,” it’s simply all the residents can afford, usually in a place where living without a car is a hardship.

Please note: we are not saying that good streets must be expensive. Good streets are for everyone. They shape the public realm where public life takes place and city residents meet each other every day. The luxury towers in Figure 1.27 do not make good public spaces or create the great city where most New Yorkers want to live.[TKTKEN39]

On March 15 I tweeted, “If America hadn’t decided to create a new national transportation system based on individuals in private cars driving everywhere for everything, climate change would be a very different—and smaller—problem than it is.”

I posted the Tweet on a couple of listservs for urbanists and followed up with some notes, comments, and questions in reaction to comments on the listservs. Some of the answers about data exist in various places. But frankly I’m not great at looking up data, so I wanted to run this by people. At this point, I’m intentionally avoiding extending the comments into conclusions.

New York City plans to spend more than $10 billion on a project that will speed up climate change and increase the number of New Yorkers killed by traffic and pollution. The good news is that the city will hold meetings so the public can comment on the plan, which is rebuilding the Brooklyn–Queens Expressway (BQE). The New York City Department of Transportation commissioned three schemes for discussion: the designs are good, but the concept is wrong. Now is the time to say so. Future public meetings are listed at https://bqevision.com/events.

Continue Reading at NYDailyNews.com<

Download Progressive Preservation Article: AfricanAmericanClassicismChas

Download Expanded Article: Classicism in the African American Community

These downloads were made available for download with the author’s permission.

A Car-Free Brooklyn Bridge Is Possible Images and Illustratons

AFTER: Aerial view looking east towards a car-free Brooklyn Bridge. Centre Street and Park Row next to the Brooklyn Bridge are reimagined as an extension of City Hall Park. © 2020 Massengale & Co LLC, rendering by Gabriele Stroik Johnson.

Continue reading

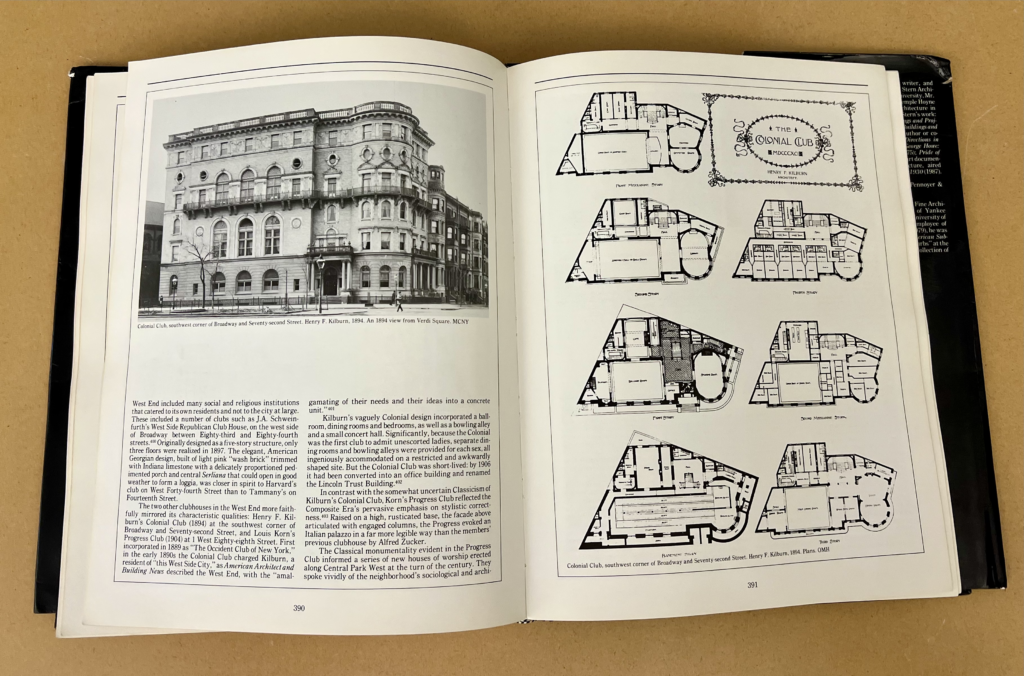

A photo of New York 1900. showing two of the four images of the Colonial Club in the book. We included so many images of the pleasant but unremarkable building because that was where we wrote the book, in Robert A.M. Stern Architects’ first office. On the southwest corner of Broadway and 72nd Street, 200 West 72nd housed RAMSA for many years in the former Ladies Dining Room of the club (illustrated on page 391).

After the club closed, a number of developers had offices in the building, including the prolific Paterno Brothers and the Cuban Holding Co. Architects in the building serving the developers included Rosario Candela and Geo. F. Pelham, the architect of my apartment house.

ONCE upon a time, long, long ago, I was lucky enough to get a summer job with Robert A.M. Stern while I was in graduate school. Stern’s new memoir, Between Memory and Invention: My Journey in Architecture (MonacelliPress, 2022), has prompted my own mini-memoir, with some relevant details not included in the book.

I arrived at the office in the early summer, not long after the dissolution of Bob’s marriage and then his office, Stern & Hagmann. I found two young architects-to-be, a sweet but disorganized secretary-receptionist-bookkeeper, and Bob. The office grew during the summer and beyond—and today there are over 200 in the office, including 16 partners in Robert A.M. Stern Architects (aka RAMSA).