WE ALL UNDERSTAND why so many normal, rational New Yorkers can act like NIMBYs—because we’ve all seen alien, intrusive development in New York like Billionaire Row and Atlantic Yards. Recent developments at the American Museum of Natural History brought this to mind, because multiple neighborhood groups are opposing the latest building proposal from the venerable, much-loved institution.

I commented on the situation in a discussion with a group called New Yorkers for a Human Scaled City (a good idea if ever there was one—if you wonder what that means, they will soon be showing the film The Human City on Thursday, May 26). One of my points in the discussion was that good urban design can sometimes be in conflict with preservation and conservation. After all every street and block in New York City (and London, and Paris, and Rome, for that matter) replaced open space and beautiful trees. When we built Grand Central and the Dakota, New Yorkers felt they were part of a city getting better and better. A problem now, as I mentioned, is that these days we think that what we’re losing is better than what we’re getting, with good reason. But there are principles of urban design, building design, and placemaking that we should look at when we discuss what to do in our cities. The current emphasis on “innovation” and bling has left many of use cold, but if we live here we are probably also city lovers. And cities are made by us. The “property rights conundrum” mentioned below is a red herring if what the museum does is also what is best for the city and its citizens.

Here’s my opening comment in discussion below. Scroll down if you would like to read more:

“There’s no question that the four teams of architects who worked on the museum (in order—Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould, Cady, Berg & See, Trowbridge & Livingston, and John Russell Pope—all good architects) would want the building completed as a solid rectangular mass, with the northern and western sides making continuous street-walls similar to the southern and eastern sides. That is what each showed in their respective master plans, and that follows traditional principles of architecture and urban design that have been increasingly ignored by the museum in the work it has done on the building since World War II. Looking at the complex from Columbus Avenue now, it resembles a person with their pants pulled down, exposing their backside.[see first photo in this article]”

You can also read the article at TribecaTrust.org.

A Wrinkle in the Debate over Theodore Roosevelt Park

As the battle to save the Theodore Roosevelt Park wages on, I’d like to take a minute to present a third, as yet unmentioned take on the matter. With sincerest desire to not torture the park advocates – who may have a legitimate case about the seizure of park land – I’d like to present a third point of view. As with every situation, there is always more than one side to a story.

Recently, there has been an on-line discussion between John Massengale*, Jeremy Woodoff** and Lynn Ellsworth*** debating the merits of a return to the original Master Plan of the museum site versus the preservation of the current park space. Ms. Ellsworth defended the notion that park space is public land, a public asset, and said that ad-hoc seizure of it by any institution is problematic. Mr. Massengale and Mr. Woodoff pushed back with an as-yet-untalked about idea, namely, that it would be better to complete the original Master Plan. Hmmm.

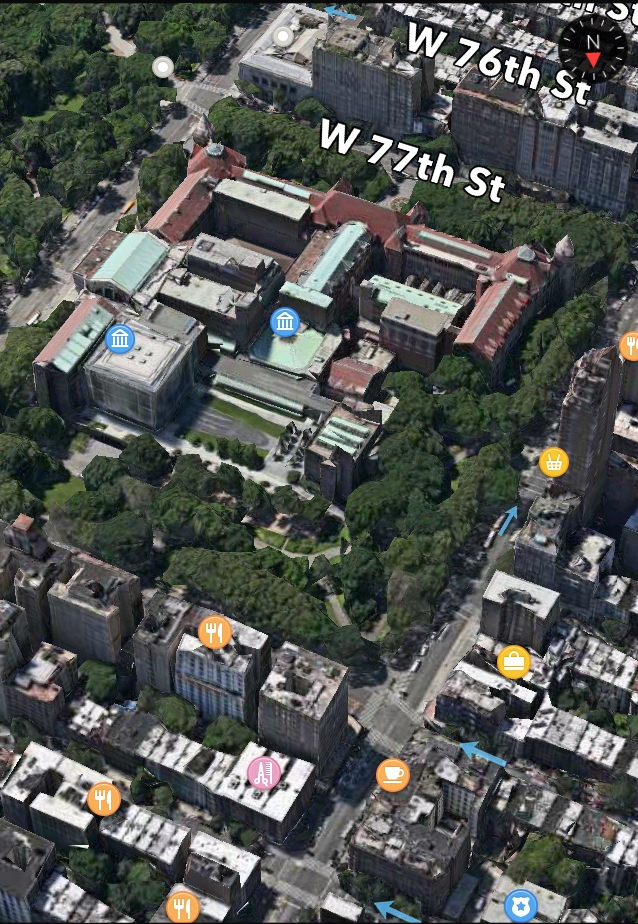

Here is a photo of the existing conditions. You can see that it looks very much “unfinished” with awkward infill in what were originally courtyards.

Remember that the land at what was called Manhattan Square was purchased by the city and management of the property was given over to the Department of Parks in 1869 to build as they saw fit. The city owned the land & buildings, and the museum owned the collections housed within. This represents a deeply intriguing property rights conundrum: much of the eventual outcome may actually hinge on how to interpret those rights.

Currently, the museum is trying to expand and occupy the green space in ways that are not even remotely congruent with the original plans of the museum or the current fabric of the neighborhood. Multiple neighborhood groups are making their voices heard in regards to the new development plans at the museum and the potential loss of park space surrounding the existing building. Here is a photo of the proposed expansion.

Click here (and then scroll down) to see an aerial view of what the proposed extension will look like from on high.

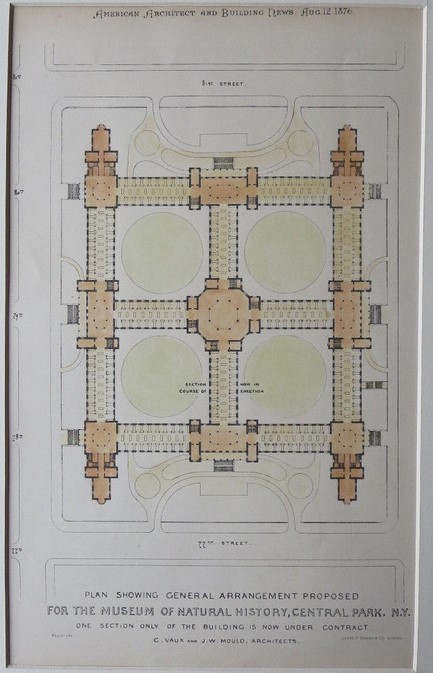

Now let’s look at the twist to this discussion offered by Massengale and Woodoff. They ask, what would it mean to have a completed Master Plan, and what does that look like? Here is Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould’s original plan as it appeared in American Architect and Building News, Aug. 12, 1876

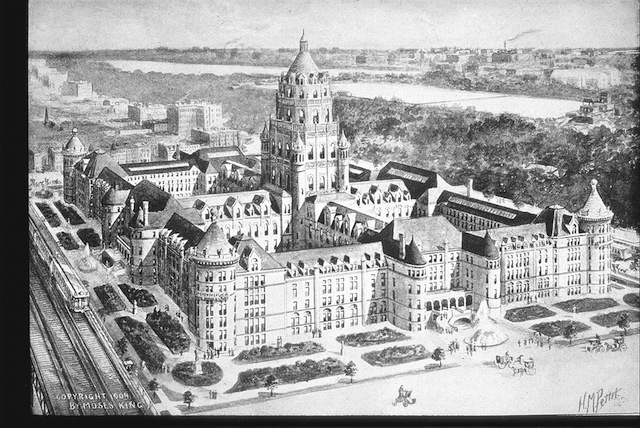

And here is a perspective view of the building, from one of the Moses King books, as it would have looked completed with Josiah Cleveland Cady’s Romanesque Revival style (Cady was one of the second team of architects to work on the building).

And here is John Massengale’s photoshopped aerial rendering of the completed Master Plan in today’s landscape.

Mr. Massengale argues that,

“There’s no question that the four teams of architects who worked on the museum (in order—Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould, Cady, Berg & See, Trowbridge & Livingston, and John Russell Pope—all good architects) would want the building completed as a solid rectangular mass, with the northern and western sides making continuous street-walls similar to the southern and eastern sides. That is what each showed in their respective master plans, and that follows traditional principles of architecture and urban design that have been increasingly ignored by the museum in the work it has done on the building since World War II. Looking at the complex from Columbus Avenue now, it resembles a person with their pants pulled down, exposing their backside.[see first photo in this article]”

and in a follow-up email Mr. Massengale added:

“For those who don’t know me, I am literally a tree-hugger—I have been known to go into Central Park and Riverside Park and hug trees. I have a particular love for American Sycamore and London Plane trees, some of which sit within the footprint of the building now proposed by the museum (although the plan is actually warped to save a tree or two). But I support the vision of the museum developed by Vaux, Mould, Cady, Trowbridge, and Pope, which would require the removal of trees that fit within the planned footprint of the building. I realize some in the neighborhood oppose any decrease in the amount of green space now on the block. But I think that idea ignores the principles of successful placemaking and good urban design that Vaux, Mould, Cady, Trowbridge, and Pope envisioned. Pope’s plan came more the 50 years after the original sketches, but like all the architects who came before him, he agreed on the vision that we see on the eastern and southern sides of the building. A vision they wanted continued on the northern and western sides.”

“Since World War II, the museum has followed a more ad hoc vision for the very large and still incomplete building. The currently proposed addition, designed by Jeanne Gang, actually zigs and zags to to save one or two trees. We can argue about the appropriateness and beauty of the proposed architecture, but we can also say that it is one more post-war addition that makes little attempt to unify the ongoing construction of the museum and its place in the neighborhood. in current architectural parlance, it is an Iconic Object, that intentionally separates itself from the image of the museum at the same time that it simultaneously reinforces and breaks down the facade on Columbus Avenue. Unlike Pope’s grand entrance on Central Park West, a Classical element added to the Medieval mass of the museum, Gang’s design is more about the expression of Gang’s challenging aesthetic than the creation of a coherent whole. In the end, it contributes as much to the incomplete backside of the museum as it adds.”

“Pope successfully unified the Central Park West facade while adding a new Classical element. Gang could similarly add a Modern element that would point the way to more unified future development of the museum. Zigging and zagging to save a tree or two leads away from that, though, and so does the idea that completing the greatest museum of natural history in a unified and beautiful way can not add as much to the life of New York as a little less green space around the museum.”

“’Green space’ is not the same thing as a park. Despite the beautiful trees between the museum and Columbus Avenue, the space there is neither a good park nor a good public space. The way that land slopes down from the avenue to the incomplete buildings is not good placemaking—which is why the space is not well used. I live on the Upper West Side, and I have noticed over the years that I have unconsciously avoided walking alongside the museum on Columbus Avenue, despite the beautiful Sycamores, and even though I like Columbus north and south of the museum. And on recent visits I have observed that the space does not attract many users, even for just sitting under the trees.”

“We are increasingly learning from neuroscience and books like The Happy City that there are places where people feel good that attract them, and places with weak or bad urban design that people avoid. Saying that we should preserve every tree in a place like that no matter what is a classic example of not seeing the forest for the trees. Making a better building and park there would also make the experience of Columbus Avenue better, even at the expense of losing some beautiful mature trees. That was the idea 100 years ago, and it’s still the best idea today.”

Mr. Woodoff is also in favor of returning to the original master plan. But he raises a question in regards to practicality.

“The original master plan was followed faithfully for over 60 years; stylistic and other “superficial” changes notwithstanding. I think this is important because it speaks to the historic and practical significance of the original plan, which served the museum so well over such a long period. The question now is, with the ad-hoc additions that have been made in the years since, does this plan still have relevance?”

And he might have a point. The plan was a great plan, but what are the chances that it would be followed today on this public land? Even if some of the trees, dog run, and other park space remain to some degree, (as Mr. Massengale’s rendering shows) would the new architects let go of their egos enough to let this original plan come to fruition? Would the museum even do it, committed as they are to a Disneyification of the experience of being in the museum? And the park land issue is serious and unresolved: what rights does the museum have to encroach on parkland?

Clearly, this is an oversimplified look at an intensely complex issue. But these are questions that we should all be thinking about. What constitutes preservation? Should we preserve only green space? Should we preserve only historic integrity? Now we have a valuable third point of view to the discussion:

- The AMNH’s desire to make highly intrusive additions that don’t follow the original master plan, seemingly designed to turn the place into more of a Disneyland than it already has become

- The view of residents who don’t want seizure of public park land for AMNH

- The argument of adherents of the original master plan of the building that a more classical build-out is called for.

Mr. Woodoff concluded with this thought:

“As you state at the end, the issue is complex. While preservation of open space is certainly part of it, so are questions of architecture (how to finish this poor building with its exposed backside) and urban design (how the building should relate visually and programmatically to the neighborhood in which it sits). The old master plan, which served four sets of architects for such a long period, should not, in my view, be relegated to a historical artifact, but should be looked to for guidance and inspiration, even if it no longer can serve as an actual blueprint.”

* John Massengale is an architect and urban designer, co-author of two books relevant to this discussion: New York 1900, Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism, 1890-1915 with Robert A.M. Stern and Gregory Gilmartin; and Street Design, The Secret to Great Cities and Towns, with Victor Dover. He is also the Chair of CNU NYC, the local chapter of the Congress for New Urbanism, which the New York Times called “the most important phenomenon to emerge in American architecture in the post-Cold War era.”

** Jeremy Woodoff is an Associate City Planner at the Historic Preservation Office of the City of New YOrk Department of Design and Construction. He was Deputy Director at the Landmarks Preservation Commission for 20 years.

*** Lynn Ellsworth is Chair of Tribeca Trust and a co-founder of New Yorkers for a Human-Scale City and in her non-civic life has done research on the emergence and institutional maintenance of common property rights.