What’s the difference between traditional and neo-traditional design? Probably not what you think. More on traditional and neo-traditional design after the photos.

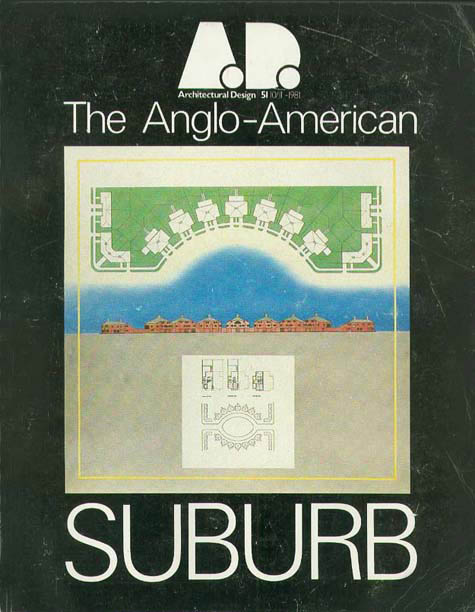

Neo-Traditional:

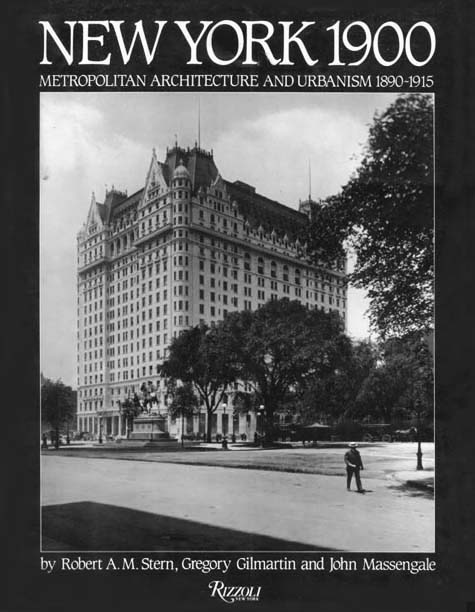

Traditional:

Traditional:

Neo-Traditional:

Traditional:

Neo-Traditional:

Traditional:

Neo-Traditional:

Neo-Traditional:

Traditional:

Traditional:

When Mazda created the Mazda MX-5 Miata in the late 1980s, they designed a body that was almost an exact copy of the 1962 Lotus Elan, a classic British Sports car. When BMW set out to revive BMC’s iconic Mini Cooper in 1998, they looked to the original 1958 design. “We wanted the first impression when you walk up to the car to be ‘it could only be a Mini,'” said BMW’s Director of Design for the project. In the same year, Volkswagen came out with another retro design of an iconic car, “The New Beetle.”* Soon after, the enormous success of the Mini led to the 2007 rebirth of the 1957 FIAT Cinquecento as the FIAT 500.

An important point: Of course the Lotus Elan, Volkswagen Beetle, and Mini Cooper are all examples of Modern industrial design (which is significantly different than Victorian industrial design). Complex machines designed to be driven, they are not traditional in the way a Georgian house or Regency carriage was. But they were all designed by individual, famous engineers—Colin Chapman, Ferdinand Porsche,and Alec Issigonis—known for their aesthetics as well as their engineering. The design of the Cinquecento was a more collaborative effort led by the engineer Dante Giacosa, in a company culture that prided itself on putting engineering first.

The four cars charm people on first sight. And although they are not strictly “traditional,” their looks and character appeal to people who also like traditional design, in a way that the 1950s Cadillacs with fins or the newest top-of-the-line BMWs or Mercedes don’t. That’s similar to the way that many of the buildings of the early Modern Masters like Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Alvar Aalto (architects who had traditional architectural training) have more in common with traditional designs than the work of Starchitects like Zaha Hadid.

All four cars are traditional in their balance of beauty, function, and construction. An analysis of their designs shows they have Classical harmonic proportions, as well as a harmony and simplicity of detail (which relates both to traditional design and industrial design as practiced until recently by Volkswagen and Mercedes-Benz). Even their sinuous curves can be found in Classical sculpture and painting.

The design philosophy behind the Miata, the new Mini, the New Beetle, and the 500 was very different than the philosophies that created the Elan and the original Mini, Beetle, and 500. Some call them “retro,” but they also show the difference between Traditional and Ne0-Traditional design.

At this point, it’s useful to shift gears and to refer to Carroll William Westfall’s discussions of the Classical and the Neo Classical. Westfall is the former Chair of the Department of Architecture at the University of Notre Dame, which teaches contemporary Classical design. Looking at Classicism as a living tradition, rather than as an historical style that ended with the hegemony of Modernism, gives Westfall a different perspective than most of us who grew up in the second half of the twentieth century, which was the age of Modernism.

In Westfall’s book Architecture, Liberty and Civic Order: Architectural Theories from Vitruvius to Jefferson and Beyond, Classicism is not a series of architectural styles—Greek, Roman, Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, Greek Revival, etc.—but a design philosophy based on principles found in nature, such as harmonic proportion and symmetry. Or in his words, Classicism is the imitation of Nature. That’s consistent with the practice of Classicism from the Greeks and the Romans to the great architects of the American Renaissance like McKim, Mead & White and Daniel Burnham, as well as with commentators like Vitruvius, Palladio, and Thomas Jefferson.

Similarly, Neo Classicism is not an historical style, but an imitation of Classical buildings rather than Nature. Neo Classicism can be done well or badly. The best examples of Neo Classicism combine a knowledge of earlier Classical buildings with an understanding and fluency in the principles of Classical design (the imitation of nature).

With that understanding, which is very different than the philosophy taught in most architecture schools today, the Miata, the new Mini, the New Beetle, and the 500 are imitations, in the best sense, of the Elan and the original Mini, Beetle, and Cinquecento. They refer to the visual character of their models, and update the cars with both a more contemporary feel and all the new technical requirements such as crash testing, pollution control, and all the “mod cons” like air conditioning and more room for everyone.

The succession of VW Golfs, on the other hand, shows the continuous evolution of one design over time—which is an important part traditional design. Until the philosophy of Modernism declared traditional design to be of the past and consequently outdated, traditional design constantly evolved, incorporating new methods of construction, new artistic attitudes, and even new locations, so that a Georgian house built in England in 1760 is quite different than a Colonial Georgian house built the same year in Charleston, South Carolina or Portsmouth, New Hampshire. At the same time, they’re all recognizably Georgian, and anyone familiar with them can easily date them just by looking at them. In England, the Georgian Classical Vernacular developed into the Regency style, while in America, after the revolution, we had the Federal Style.

In Charleston, a conservative place with a motto that says Ædes Mores Juraque Curat (“She preserves her Temples, Customs, and Laws”), the local Georgian architecture evolved more slowly. Around 1750 the city developed a local house known as a Single House, which is well suited to the deep, narrow lots of the city plan and the hot, muggy, climate. But Charlestonians built the type for more than 250 years, and almost in contradiction to what I said, you sometimes have to be sensitive to the tradition to tell the difference between a Single House from 1810 and one from 1910. You can compare the two houses to the Lotus Elan and the Mazda Miata, because there are improvements in construction methods, climate and termite resistance, functional changes in the way families used the houses, and the like. You can also find Victorian Single Houses from 1870 that compare to the original Beetle and the New Beetle.

More typically, all of the British colonies that became American states have Georgian / Colonial houses, and later Colonial Revival houses that are recognizably Colonial and recognizably from the late 19th or early 20th centuries. In western states, the Colonial Revival houses frequently have more visual separation from the original Georgian houses than versions in the eastern states. But overall, the Colonial Revival became its own tradition, much like VW Golf and its successive iterations.

The evolution of the Colonial Revival began in 1877, when Charles McKim, William Mead, William Bigelow, and Stanford White went on a tour of New England architecture inspired by the American Centennial a year before. They traveled up the Atlantic coast, sketching 18th century houses—but mainly drawing the backs of the houses, where there had been many picturesque additions. This appealed more to the taste of the time than the simple, often severe fronts of the houses. The four architects published their sketchbook and developed what came to be known as the Shingle Style. They eschewed the complex patterns and massing of the Eastlake style of Queen Anne architecture, but designed billowing masses with simple shingle expanses joined with complex porches and roofs.

By the early 1990s, however, McKim, Mead & White were purer Classicists. They designed some of the first skilled and scholarly Colonial Revival houses, which became the most popular house type in America, moving the Colonial Revival from Neo Traditional to Traditional.

* In the 1999 Car of the Century competition to determine the world’s most influential car in the 20th century, the Beetle came in fourth, after the Ford Model T, the Mini, and the Citroën DS.