“An American Renaissance Gem, How an industrialist

and his unlikely team built a Miami marvel”

The Wall Street Journal, December 9, 2006; Page P13

Book review by John Massengale

Vizcaya, An American Villa and Its Makers

By Witold Rybczynski and Laurie Olin

Penn Press, 274 pages, $34.95

Some of our greatest buildings are not as well known as they should be. How many people outside of Atlanta are aware of Swan House, the best design by that city’s best classical architect, Philip Trammell Schutze? And if you haven’t been to Miami, you probably don’t know the Villa Vizcaya, a country house that is the equal of any in America.

Both houses, like many of the best American buildings and neighborhoods, were built roughly a century ago during the time of the American Renaissance and City Beautiful movements. The American Renaissance was a “rebirth” of classical art and architecture in the U.S.; the City Beautiful was an urban design and reform movement. The Depression slowed both American Renaissance and City Beautiful, and World War II brought them to a halt. When the war ended, modernism had vanquished their traditional architecture and urbanism.

To the winners go the spoils: Histories of early 20th-century American art and architecture were written by modernist proponents who criticized the achievements of the American Renaissance and City Beautiful designers or ignored them altogether. The preservationist James Marston Fitch, founder of the historic-preservation program at Columbia University (the first and most prominent preservation program in the U.S.), spoke for many when he dismissed the American Renaissance as “an aesthetic wasteland,” populated by buildings that were “a reactionary application of eclecticism” that “ultimately smothered all traces of originality.”

Vizcaya: An American Villa and Its Makers, by architect Witold Rybczynski and landscape architect Laurie Olin, is one of a number of popular and scholarly histories that in the past two decades have sought to redress this ideological imbalance. Mr. Rybczynski and Mr. Olin judge the villa as they find it today and in the context of the historical process that produced it, rather than through a filter of modernist criteria. Contrary to Fitch’s judgment, they find that the eclectic team that built Vizcaya produced a work of great and original beauty.

It is not surprising to find originality and beauty in the American Renaissance. What is surprising is that this great achievement was “the work of three neophytes,” according to Mr. Rybczynski (who wrote “Part 1: House”; Mr. Olin wrote “Part 2: Garden and Landscape”). Mr. Rybczynski describes this trio, Paul Chalfin, F. Burrall Hoffman and Diego Suarez, as “a failed painter and art scholar whose creative legacy is chiefly this one great project; a young architect who never built anything of similar consequence—before or after; and a 25-year-old gardening dilettante who became involved in the project more or less by accident.”

To that list we should add the client, an industrialist named James Deering. A founder of the Deering Harvester and International Harvester companies, the semiretired Deering made the design and building of Vizcaya his primary job, managing the construction of the house and of its extraordinary gardens in much the way he had managed his companies.

Early in the process, Deering hired Chalfin, the “failed painter.” Together they traveled to Europe not only to look at villas and chateaus but also to buy bits and pieces of them—doors, mantels, ceiling paintings and whatever else appealed. Chalfin introduced Deering to Hoffman, a talented architect in New York who had the skills to put the rooms envisioned by Chalfin and Deering into a beautiful, coherent whole. It was on Chalfin and Deering’s travels in Italy that they met Suarez—a Colombian-born landscape designer who learned his trade by restoring Italian gardens.

Chalfin outlasted both Hoffman and Suarez on the project, to some degree pushing them out of the way so that he could both supervise construction of the house and gardens and take credit for the work. We now know that Suarez drew up many of the original ideas for the gardens, despite Chalfin’s claims to the contrary years later. But that is not to minimize Chalfin’s contributions: Deering later said that he “was responsible for 90% of the beauty” at Vizcaya.

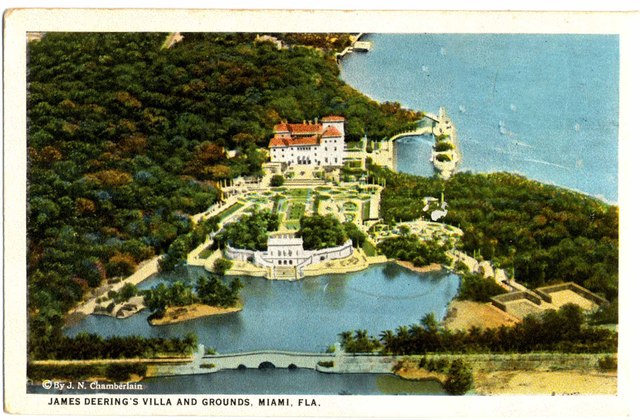

The greatness of the Villa Vizcaya comes from the team’s skillful integration of beautiful classical forms with the local conditions in Miami, the only subtropical city in America. The way the house welcomed the outndoors in, the adaptation of Italian garden principles to a flat Florida swamp and the siting of the house next to Biscayne Bay—all of this, combined with classical house and garden design, resulted in a work of genius.

Most Florida mansions at the time were built back from the sea on a low limestone ridge that ran slightly inland from the shore along the coast south of downtown Miami. But Deering wanted the house near the bay, and the team put the villa in a mangrove swamp right on the water. Italian gardens usually have hillside terraces, but Suarez and Chalfin transformed the low, flat swamp into the best Italian-style garden in America, with only a small amount of fill.

The garden alludes to Italian hillsides with minimal means. The approach to Vizcaya leads the visitor down from the ridge to the house, visually emphasizing the change in grade. The formally laid-out garden terraces to the south of the house have slight differences in elevation, but the house sits above them, raised on a basement hidden by patios at the level of the first floor. Across the garden from the house is a small building, a casino, on a man-made knoll, which gives the illusion of a hilly topography while blocking sunlight glaring off the water beyond. Most important, the gardens were beautifully designed and planted. Not all the plants that Deering wanted could thrive in Miami. But through trial and error, Chalfin and Deering arrived at solutions that worked beautifully.

The house itself had an open-air courtyard, intimately connected to the gardens and the sea by large rooms that could be opened in such a way that no walls interrupted the flow of people or air from the patios to the courtyard, which was filled with sun and palm trees. Arcades around the court functioned as open-air hallways.

In the 1950s, Deering’s descendants sold Vizcaya to Miami-Dade County for $1.4 million, at the same time donating the villa’s furnishings, also valued at $1.4 million. The house is now a museum, and the county frequently rents out its rooms and gardens for parties and receptions. In the 1980s, the county roofed the courtyard in order to air-condition the house, to preserve its fabrics and furnishings, and to make it more suitable for events. Many Miami architects, including the New Urbanist Andrés Duany, protested the closing-in of the courtyard. To no avail: The house is now sealed and air-conditioned, deprived of its direct connection to the sea, the gardens and the Florida air. The courtyard, which was supposed to be a breezy, sunlit outdoor space at the heart of the estate, is now a dimly lit interior room covered by a heavy an obtrusive steel and glass roof. Vizcaya is still spectacular, but it has lost some of its Florida genius loci. One of the authors of a recent conservation study funded by the J. Paul Getty Museum, University of Miami professor Rocco Ceo, recommends that the roof be removed.

Mr. Rybczynski and Mr. Olin do an admirable job of conveying the history of Vizcaya, but their book is not one of those lavishly photographed, coffee-table architecture books that have become so common in recent years. “Vizcaya” has old photographs of the house as it was and new ones by the Miami architectural photographer Steven Brooke, but we wish we could see more and larger photographs and illustrations of such a beautiful place.

Mr. Massengale, an architect and urbanist, is the author, with Robert A.M. Stern and Gregory Gilmartin, of New York 1900, Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism 1890 – 1915. He is a visiting critic at the University of Miami and the University of Notre Dame.

Reprinted with permission of The Wall Street Journal © 2006 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Originally posted in Veritas et Venustas on 12/10/08