A YEAR OR SO AGO, I was invited to take part in a discussion on Traditional and Modern architecture at theglasshouse.org that was framed like this:

Traditional versus modern architecture; Proponents of traditional architecture cite a preference for historical styles. Modernist proponents, myself included, prefer architecture that responds to its larger contemporary context.

Where do you stand on the traditional versus modern debate, and why? Is there a contemporary compromise?

My response, below, was to talk about the architecture of time versus the architecture of place:

My interest here is not about style. I like all sorts of towns, cities and buildings, but what I design are Classical buildings and traditional towns and cities.

“Classical” does not mean “traditional” (or “neo-traditional”), and Classicism is a way of designing rather than a style. Most of the market doesn’t want ideological purity, and when it does, the bias is likely to be towards traditional.

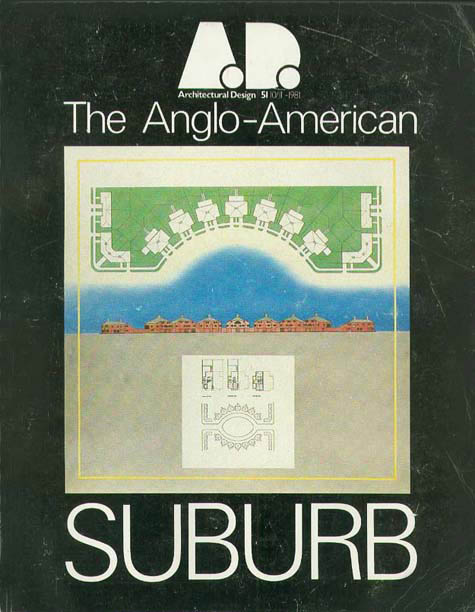

More to the point, I grew up in the suburbs but I live in Manhattan, and what I’m most interested in is the design of walkable places. To talk about that in the context of this discussion, I think it’s better to talk about an architecture of place versus an architecture of time than about style.

The architecture of time is the architecture of the Zeitgeist, the theory that has sustained Modernism for well over 100 years. Frank Lloyd Wright was born just after the Civil War and designed important houses in the 19th century, and Modernism was the dominant cultural expression in America as soon as World War II ended. I think that time has ended.

The architecture of time has produced many great buildings, but it comes with two large caveats. One, its rate of return is terrible: for every Ronchamps or Bilbao there have been hundreds, if not thousands, of very bad buildings. Great Modern design is hard to teach, and the emphasis on experimentation and “unprecedented reality” produces many experimental failures (“Architecture is invention. All the rest is repetition and of no interest,” Oscar Niemeyer said). Moreover, the architecture of time also includes all the Modernist shopping centers, strip malls, spec office buildings and the like.

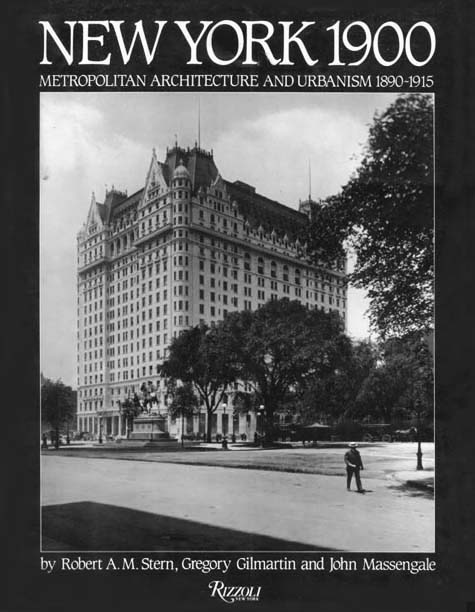

Second, the architecture of time is more about making objects than places, and Modernism has produced very few great places, and absolutely none to rival the great places like the Piazza San Marco in Venice or even New York’s Park Avenue or the typical residential street in Park Slope, Brooklyn (built almost entirely without architects or urban designers).

Periodically, publications like Time Out will ask its readers to pick their favorite street, and the winner is always a street like South Portland Avenue in Brooklyn, a street laid out by a surveyor that is straight as an arrow, with simple repetitive row houses built on speculation without the assistance of architects. Enlarge the area of discussion to the creation of towns and cities, and there’s no contest. After more than 100 years of trying, during the wealthiest period in the history of the world, where is the great Modernist city, town or neighborhood?

Modernism also tends to work best in a traditional context. The Seagram Building on Park Avenue was a glass gem in a traditional masonry setting that added variety and interest to Park when it was built.

Lever House, almost across the street, was the same. But go there today and walk south to the blocks where glass boxes have entirely replaced the earlier masonry buildings and the street loses much of its appeal to pedestrians, even though the wide street itself brings variety and sunlight to midtown Manhattan. Richard Florida’s Creative Class, which chooses the character of where it wants to live and work before taking a job, is why Silicon Alley is located downtown in neighborhoods where Modernism is still the exception rather than the rule. Like most people, Millennials like both Modernist and traditional architecture, but they clearly prefer traditional urbanism.

The architecture of place is about creating and reinforcing places where people feel good, making a public realm with comfortable outdoor “rooms.” It uses the “timeless principles” described by Christopher Alexander and Jane Jacobs to do that. These principles work across what New Urbanists call “the Transect,” the range of patterns from the densest downtown like New York’s Wall Street to the smallest walkable village or hamlet. In the 21st century, one of the most important uses for those principles is the creation of walkable, comfortable places that entice us to get out of our cars. “You can’t spell ‘carbon’ without ‘car.’” they say. Before the hegemony of the architecture of time, all architects thought their first responsibility in designing a building was reinforcing that public realm.

The object buildings, the expression of technology at the heart of the architecture of time, and the emphasis on the expression of originality usually fight against that. And the so-called “avant grade” side of the profession that dominates the academic and media discussion pursues goals that by definition means their buildings can’t play well with others. “Great buildings contradict everything else,” fashionable architect Gregg Pasquarelli said in a discussion in New York magazine about the best buildings in New York. “Maybe that’s what a city is: confrontation and complication. In New York, the name of the game is to have one’s own envelope,” his former Dean at Columbia replied. The builders and architects who made the New York we love—like the developers of Park Slope and the architects like McKim, Mead & White who built our great monuments like Penn Station—believed exactly the opposite.

I was born in New York and the suburbs I grew up in were less than 10 miles away from Philip Johnson’s Glass House. After I got my driver’s license, I used to sometimes go peer over the wall at the edge of the property, and once or twice Johnson came out and shook his fist before I drove away.

The Glass House is a great work of architecture, and one of my favorite buildings. It is a folly in the woods that draws on lessons of history, but it is also an object building and resolute expression of the zeitgeist of the postwar time when it was built. I should say that Johnson’s zeitgeist is not mine, and one has to ask if Modernism, an architecture of time, expresses the current zeitgeist, or if it is just a style.

We are the first generations in the history of the world who realize that the way we build will determine the future of our planet, for better or for worse. We need walkable and sustainable cities, towns and neighborhoods, and that is overwhelmingly what the young want. They’re happy with many styles, but they want cities and towns where they can lead their lives without cars. More important than the style of second houses for the rich in the Hamptons is the construction and reconstruction of urbanism where people want to be.

Towards that end, at this time Modernism needs to over- come its obsession with the expression of technology and the creation of controversial objects. The fixation on the aesthetic perfection of the energy-wasting glass curtain wall is irresponsible towards future generations, and the idea that the style of a design by Jean Nouvel for obscenely expensive Manhattan pied-a-terres for the super-rich is somehow a progressive action is delusional, anti-social, and anti-urban. The discussion of how to make and reinforce places that are environmentally, economically, and socially sustainable is much more important than talking about architectural style. But style in the broadest sense, the style and character of buildings that people love and that make good urbanism, can be a big part of that discussion.