I RECENTLY spent a week in Seaside, where I was once Town Architect. In honor of Seaside, I’m uploading two essays from Street Design, The Secret to Great Cities and Towns. The first is the opening of the chapter on new streets:

Chapter 5, New Streets

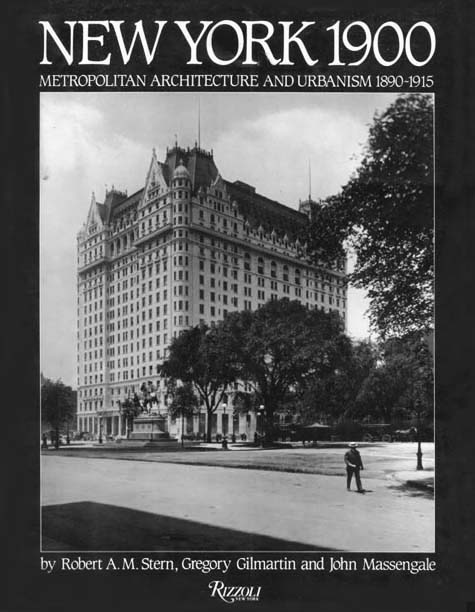

TWO VERY DIFFERENT DEVELOPMENTS from the early 1980s are important landmarks in the recent history of urban design and street design. Battery Park City, a ninety-two-acre extension of Manhattan in the Hudson River that was built on landfill from the construction site of the World Trade Center, has office towers, mid-rise and high-rise apartment buildings, and stores. Seaside, Florida, an eighty-acre development on the Florida panhandle, is a resort built in the form of a town. What the two places have in common is that their streets were designed with many of the placemaking principles outlined in this book. Both projects were a radical departure from the conventional practice of the time. The histories of both demonstrate how auto-centric regulations across the country hinder the making of good streets.

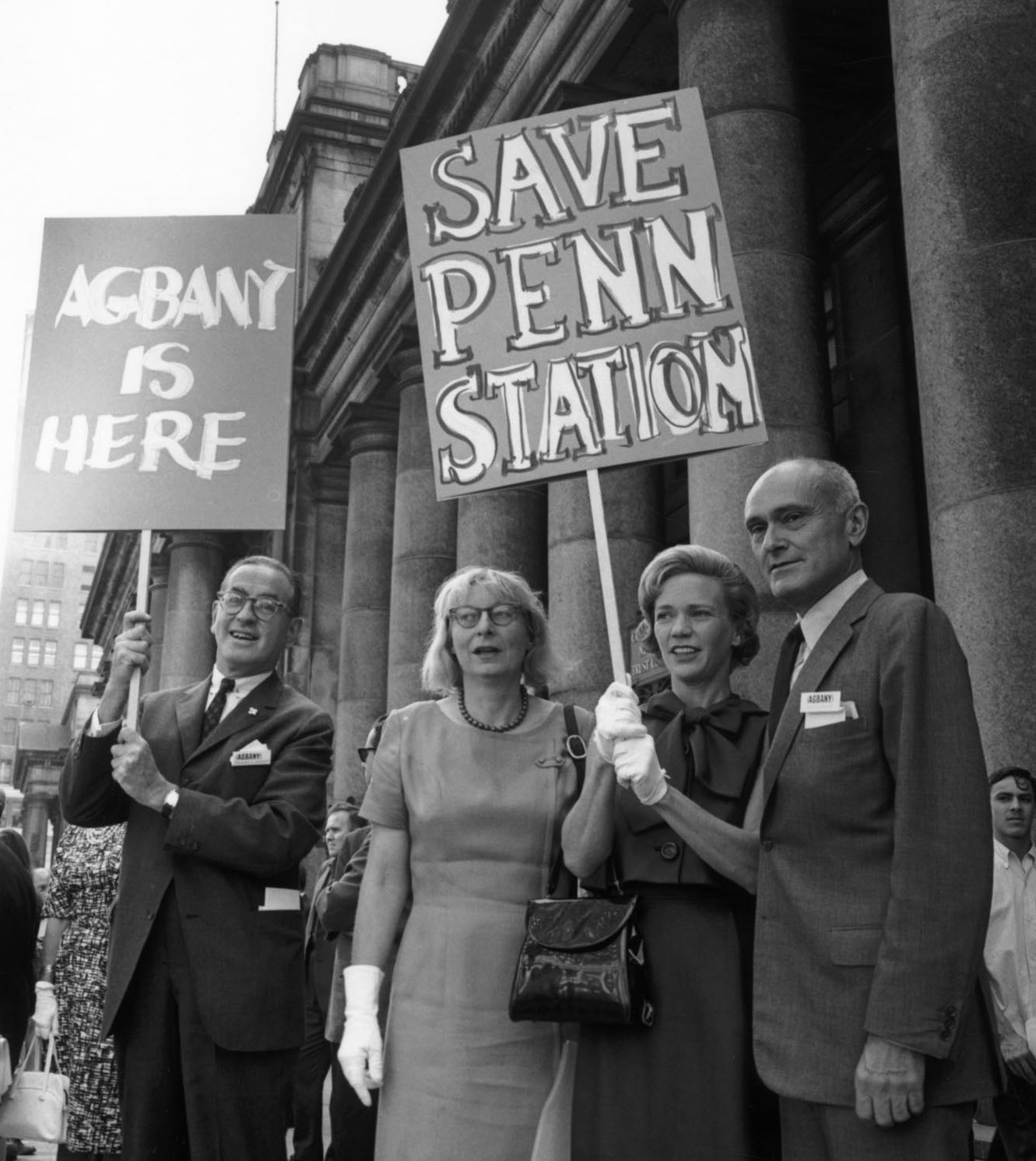

It wasn’t that people didn’t understand the principles; by the early 1980s, they had been talked about and praised for at least two decades. Jane Jacobs wrote the enormously popular The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961, Bernard Rudofsky published Streets for People1 (also very popular) in 1969, and William H. “Holly” Whyte had been publishing his influential studies of how people use urban space since the late 1960s.2 Despite professional acceptance of the theories, however, most of the sprawl in America was built after the publication of Death and Life. Many planners endorsed these works, but the American Planning Association and its members continued to promote regulations based on an auto-centric separation of uses, with road standards established by the engineering profession’s anti-urban functional Classification system. “The pseudoscience of planning,” Jacobs wrote, “seems almost neurotic in its determination to imitate empiric failure and to ignore empiric success.3 Continue reading →