WE ALL UNDERSTAND why so many normal, rational New Yorkers can act like NIMBYs—because we’ve all seen alien, intrusive development in New York like Billionaire Row and Atlantic Yards. Recent developments at the American Museum of Natural History brought this to mind, because multiple neighborhood groups are opposing the latest building proposal from the venerable, much-loved institution.

I commented on the situation in a discussion with a group called New Yorkers for a Human Scaled City (a good idea if ever there was one—if you wonder what that means, they will soon be showing the film The Human City on Thursday, May 26). One of my points in the discussion was that good urban design can sometimes be in conflict with preservation and conservation. After all every street and block in New York City (and London, and Paris, and Rome, for that matter) replaced open space and beautiful trees. When we built Grand Central and the Dakota, New Yorkers felt they were part of a city getting better and better. A problem now, as I mentioned, is that these days we think that what we’re losing is better than what we’re getting, with good reason. But there are principles of urban design, building design, and placemaking that we should look at when we discuss what to do in our cities. The current emphasis on “innovation” and bling has left many of use cold, but if we live here we are probably also city lovers. And cities are made by us. The “property rights conundrum” mentioned below is a red herring if what the museum does is also what is best for the city and its citizens.

Here’s my opening comment in discussion below. Scroll down if you would like to read more:

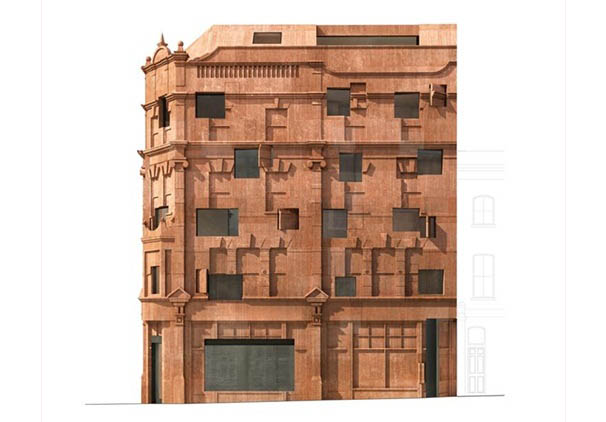

“There’s no question that the four teams of architects who worked on the museum (in order—Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould, Cady, Berg & See, Trowbridge & Livingston, and John Russell Pope—all good architects) would want the building completed as a solid rectangular mass, with the northern and western sides making continuous street-walls similar to the southern and eastern sides. That is what each showed in their respective master plans, and that follows traditional principles of architecture and urban design that have been increasingly ignored by the museum in the work it has done on the building since World War II. Looking at the complex from Columbus Avenue now, it resembles a person with their pants pulled down, exposing their backside.[see first photo in this article]”

You can also read the article at TribecaTrust.org. Continue reading