Yes, Staten Island, my birthplace

Click on any of the images for a larger view

Click on any of the images for a larger view

THE MYSTERY LOCATION is Historic Richmond Town, on Staten Island. I like the house because of it’s simplicity, harmony, proportions, composition, materials, colors—and the beautiful street trees.

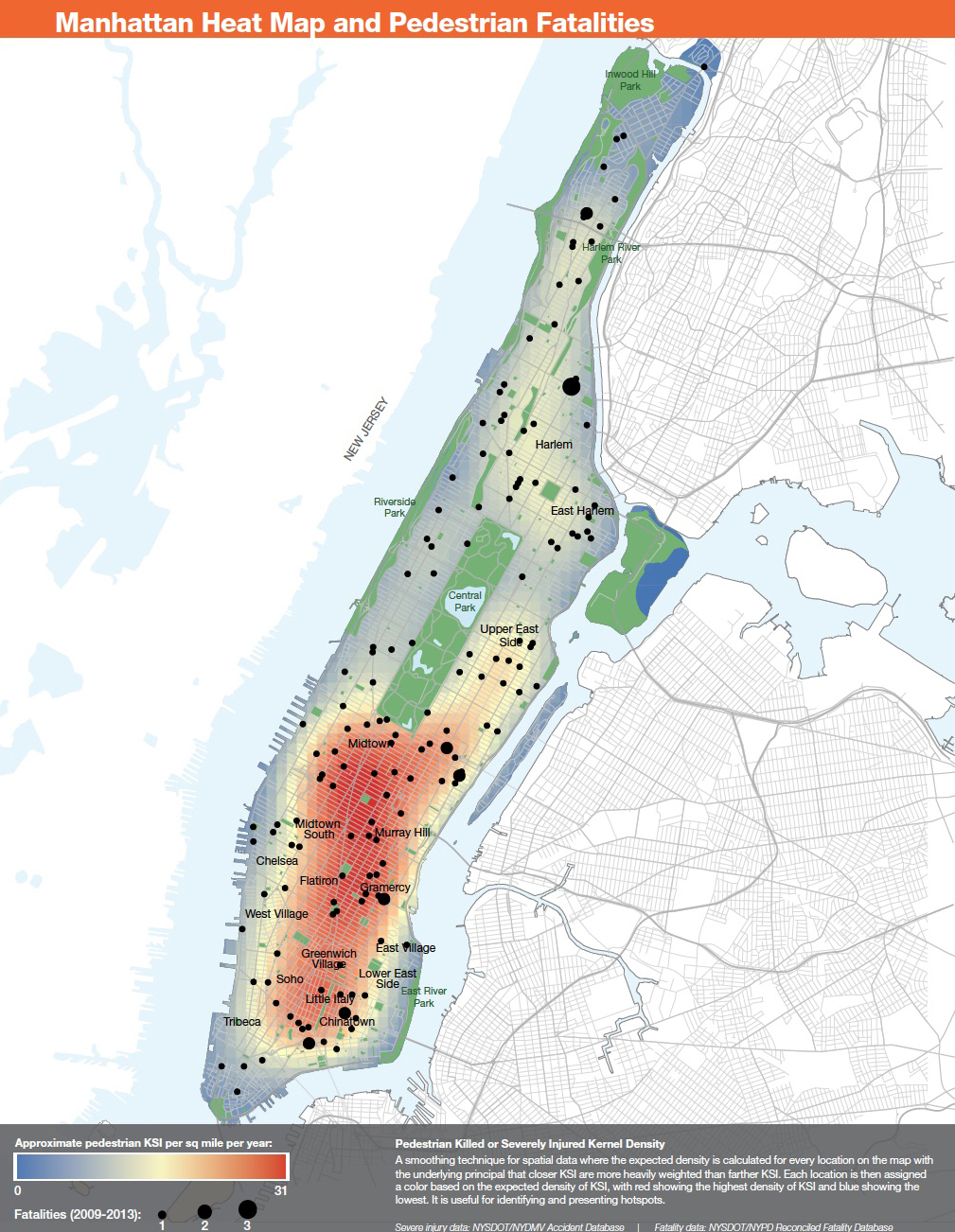

Map of the Day

THIS NEW MAP from the NYC DOT shows where pedestrians are killed in Manhattan. The overwhelming majority of the deaths happen to city residents who don’t own cars, to workers in the Manhattan who used public transit for their commute, or to tourists who arrived by plane, bus, or train.

If we had fewer people driving, and all people driving slowly, we could cut those deaths to zero. #VisionZero

Guess the location and win a prize

Click on any of the images for a larger view

Click on any of the images for a larger view

Continue reading

Why Condo-ization Is One Of The Two Or Three Biggest Factors In The Increasing Unaffordability Of New York City

THIS IS COMMON SENSE: Eliminate one way or another many inexpensive rental apartments and then build super-luxury condominiums targeted at non-resident foreigners who own half of all the wealth in the world and you will soon find that the laws of supply and demand will make apartments more expensive.

JULY 15: An “Interactive Map Shows NYC’s Disappearing Rent-Stabilized Apartments” has lots to look at. My current building is included. Our landlord has delisted 11 apartments, leaving us as the only rent-stabilized unit (and see here).

The explosion in the cost of apartments in New York City—rentals, co-operative apartments, and condominiums—would not have happened to the degree it did without the widespread conversion of rental apartments into condominiums and co-operatives.

Edmund Glaeser argues in Triumph of the City that increasing the housing supply always lowers prices—it is the main basis for his argument for apartment towers and hyper-density—but he ignores how quickly and directly form can follow finance, and the fact that condominiums, co-operative apartments, and rental apartments serve different markets. That is particularly true in Manhattan (and similarly in other “global cities), where a change from a focus on rental and co-operative apartments to the creation of a supply of condominiums was a necessary condition for the current state of the market, which has enormously widened to include the global 1%, who control 50% of the world’s wealth. Unlike the New Yorker, who looks on Manhattan as a place to live, the non-resident plutocrat looks on Manhattan as part of a diversified investment portfolio, for capital both legally and illegally obtained. A recent article in the New York Times shows how much new construction goes to anonymous foreign buyers, who use the condominiums to hide money from their governments and the US government. As we shall see, these buyers do not want to buy in co-opeative buildings (and usually can’t), and they are not interested in rental apartments.

This has drastically effected the rental market, which has lost and continues to lose many apartments to conversions and teardowns. The result has several aspects, which all serve to raise prices.

- In the 1970s, developers converted large numbers of rental apartments into cooperatives and condominiums. This gave them high short term returns and took many apartments out of the rental market.

- Over time, apartment seekers who did not have the money for a downpayment or the financial resources to obtain a mortgage found themselves with dramatically fewer choices.

- When this process began, there was little difference in price between the average market-rate rental and the average rent-stabilized rental. Buildings with more than six apartments were rent stabilized, and apartments stayed rent stabilized until their rent rose above a price reviewed every year by the rent stabilization board. When market-rate rents and rent-stabilized prices were similar, that was usually not an important factor in the status of the apartment.

- Condominiums became more popular, because unlike co-operative buildings, condominium boards can not reject potential buyers. Over time, condos became more expensive than coops.

- Global capitalism produced a large number of buyers around the world who bought expensive New York City condos as part of a diversified investment portfolio. New York City became an increasingly popular place for the international super rich to illegally hide money.

- Non-resident buyers and foreign investors in particular wanted apartments with long views in shiny new towers. This has produced the hyper-density of Billionaire’s Row on 57th Street, which raises rather lowers prices.

- Profits on developing condominiums grew very large and buildings with rental apartments sold as teardowns.

- Fewer rental apartments and drastically higher prices for condominiums raised rental costs. With the higher rentals, almost all rental apartments could be renovated and taken out of the rent stabilization program or sold as condos.

- In recent years, non-residents have bought 40-60% of the condos for sale in some of the more expensive Manhattan neighborhoods. This raised prices significantly several years in a row. New York has been in a building spree that has made it less affordable.

- Although he is reluctant to ascribe cause and effect, New York housing price guru Jonathan Miller points out that over the past 25 years, rise in sales price for a Manhattan apartment corresponds closely to the average Wall Street bonuses over the same period. These New Yorkers, of course, are part of the global 1%. They count for 5% of the jobs in New York City, but 25% of the income.

Today’s overheated market cannibalizes the small remaining stock of affordable apartments in old buildings, converting them or replacing them with unaffordable housing. When a rent-stabilized apartment is torn down or converted to a condominium in Manhattan, it becomes almost impossible for the tenant to find another rent-stabilized apartment on the island. It was easy when the supply of old apartments in rental buildings built for the middle class and the working class was still plentiful, but the shrinking of the supply side, the inability of the development industry to supply new inexpensive rentals in this market without subsidies, and recently, the sheer number of Manhattan apartments that shrink the availability of all apartments by selling to non-residents who rarely occupy them has radically changed the game.

The more Manhattan prices increase, the more attractive Manhattan condominiums become to foreign investors and speculators, and the more incentive there is for developers to chase those profits. The most expensive apartment in the history of New York recently sold to a hedge fund manager who intends to keep the $90 million penthouse empty until he sells it again. Soon after, a duplex apartment in the same building sold for $100 million. For the first few years all buyers in the building will get a large discount on property taxes, courtesy of tax incentives given to the developer by the Bloomberg administration.*

In this market, a scarcity of rentals makes it easy in every building but the lowest quality ones for the landlord to spend enough money renovating a vacated rent-stabilized apartment that the rent goes to the now-high market rate and becomes unregulated. Or, the landlord sells the apartment as a condominium, or tears down the building to assemble a larger parcel for a luxury tower. Even in the locations where one can not sell an apartment for $50 million, apartments costing $1 million to $10 million can often be sold.

Unsubsidized new construction south of 96th Street in Manhattan can never replace the old affordable apartments lost when land costs and contractions costs are so high. As long as we continue to lose rent-stabilized and rent-controlled apartments and apartment buildings all over Manhattan, the situation is bleak. For anyone looking for an apartment in Manhattan today, it is almost impossible to find inexpensive and appealing rentals. We used to have lots of them, but we’ve had a process for several decades that profits by getting rid of them one way or another.

* The property taxes ton the $100 million condo last year were “$17,268, according to the city’s finance office. Those taxes will go up over time, but for now that is a savings of more than $359,000.” Source: New York Times.

Architecture: I am not a Fashionista

STARCHITECTURE is both promoted and taught as the work architects should aspire to do. But really, it’s the equivalent of the High Fashion seen on the runways at fashion shows, where designers make extreme statements to be provocative and distinguish themselves among the cognoscenti.*

The man with the Lego face was photographed last month on one of the runways during London’s fashion week. No one expects that anyone will buy the costume and walk around looking like that. It exists in a world that sits on a top of a huge clothing industry, with many different options: American Eagle, The Gap, JCrew, Ralph Lauren, Tommy Hilfiger, Rag and Bone, Comme des Garçons, Tory Burch, and all sorts of brands we’ve never heard of, who sell through Target and Wal-Mart on the one hand, and small boutiques and clothing stores across the country on the other.

When you read Architect, the official publication of the AIA, or look at what architecture students are doing in most east coast or west coast architecture schools, most of the time it looks like Fashion Week. Much of the rest of the industry is often missing. MRDV’s exploding building in the second photo has been published many times. The architecture press usually praised it. The regular press was shocked that in any ground level view it looks like the World Trade towers exploding. It has almost nothing to do with the buildings designed by most architects today.

Among the many problems with this is that true art, which includes the best architecture, is made by people doing what they love. Forgetting for the moment that architecture is a public art, with a responsibility for shaping the public realm (a responsibility most “iconic” buildings ignore), architecture will be best when architects design buildings that reflect the architecture they love. Only rarely will that be “cutting edge.” I go to visit Starchitecture, and even love some of it, but it has very little to do with what I want to design. I am not a Fashionista.

* Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

The Good Kind, and the Other Kind

The top photo shows, from left to right, the Pierre Hotel, the Sherry-Netherlands Hotel, the Savoy-Plaza Hotel, the Squibb Building, and the Plaza Hotel. In between the Pierre and the Sherry-Netherlands Hotel are the Metropolitan Club and two long-gone buildings. In the background is the tower of the Ritz-Carlton.

The top photo shows, from left to right, the Pierre Hotel, the Sherry-Netherlands Hotel, the Savoy-Plaza Hotel, the Squibb Building, and the Plaza Hotel. In between the Pierre and the Sherry-Netherlands Hotel are the Metropolitan Club and two long-gone buildings. In the background is the tower of the Ritz-Carlton.

In the lower photo, the Pierre and the Plaza can be seen at the top left corner of the Park. ‘Billionaire Row,” the new New York, is less urban and urbane, even though the distant birds-eye view minimizes the effect in the smaller view. One of the first of the Billionaire Row buildings, 432 Park Avenue, is already visible from all over the city. Not just from Central Park or Park Avenue in the 90s, but from Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx.

Click on either photo for a larger view.

Live from New York – 555 Hudson Street – Jane Jacobs’ House

“Ninety-eight percent of the people who hang out in our restaurants hate glass towers”

STEPHEN ALESCH, a partner at Roman and Williams and the designer of the Ace Hotel, Lafayette, the Breslin, the Boom Boom Room, the Dutch, and many more said that last night during a talk at the ICAA.

I don’t hate glass towers, but I understand those who do. More to come on why they’re never sustainable, even the LEED Platinum ones. (Hint: Our story begins when someone sticks a thin-skinned, free-standing glass tower up in the air, where it’s heated by the summer sun and cooled by winter winds.)

The Problem Is Not The Starchitecture. The Problem Is What Gets Left Out Of The Discussion.

Mystery Street of the Day

A STREET seen in Downton Abbey last night (in America), is a CGI creation. It’s a beautiful street, so I’m curious as to what’s real and what’s new. (PS: Answers below.)

The way that the arcaded building bumps out at the top of the hill (on a square?) is quite beautiful—click on the image and zoom in and you’ll see steps going up to the arcade. Also beautiful are the stone sidewalks and street with the stone and red-brick buildings (a change from the red-brick and tinted stamped concrete ‘bricks” that so many American cities default to when they want “streetscape”).

Less Is More

SEEN ON PARK AVENUE at 63rd Street, an old Cinquecento and a Honda Odyssey “Minivan.” This photo has not been Photoshopped or altered in any way. #climatechange

Continue reading

Historic Street of the Day

BROADWAY, Saratoga Springs, New York, back when you could have any color Ford you wanted (as long as it was black), and the Dutch Elm blight hadn’t decimated America. Photograph by Walker Evans.

“All the great cities and towns are congested”

“All the great cities and towns are congested” is an urbanist trope that needs to be retired. It comes, I believe, from arguing against traffic engineers when they talk about Level of Service rather than observing the best places. There are cities and towns that would benefit from more people coming downtown, of course, but many cities and towns around the world are suffering from too many cars on their streets.

I was in London the day their Congestion Zone started. I was staying in a hotel on High Holborn, a major through street that continues Oxford Street (or vice versa, depending on where you’re coming from). The Central Line on the London Underground was under repair and wasn’t running.

The day before the congestion zone started, Oxford Street and High Holborn were jammed even more than usual with buses, taxis, trucks, and cars. You could walk any distance long or short in either direction from Oxford Circus or Tottenham Court Road and know that walking would be faster than taking a bus. They were traveling along stuck nose to tail in traffic. The problem was the speed the buses were going, not time spent waiting for a bus.

That day traffic flowed like water in an oversized pipe, just the way traffic engineers like it. But that was because traffic was restricted, of course, not because of new and more efficient changes in the streets. The lack of traffic made walking the streets so pleasant, and such a pleasant contrast to the day before. It was the way cities should be. You could walk without being buffeted by noise and diesel smell, and you didn’t have to wait at every crossing for traffic to pass by.

Slow Street of the Day – Rue Norvins, Paris

Photo courtesy of Galina Tahchieva @ DPZ

ALMOST ALL STREETS IN PARIS now have speed limits of 20 or 12.5 miles per hour (30 or 20 kph). The rue Norvins in Montmartre was already slower than that. Why? Not because of a city-set speed limit or police enforcement, but because of the natural design speed of the street.

The narrow roadway, the poor lines of sight, the rough cobblestones, the unforgiving stone bollards at the edge of the street, the lack of traffic signs (there’s only one, which limits cars to those belonging to residents between 3 pm and 2 am), and most of all, the free-range pedestrians in the middle of the street—these all produce a space that makes drivers unacomfortable driving quickly.

English authorities are introducing a number of shared space streets there. I haven’t seen most of them, so I can’t say much about the Sea of Change film that makes the proposal that new shared space streets in England are frequently unsafe for the blind and disabled. That’s obviously an important issue—if we are going to make slow streets that use slow speed and a lack of the traffic engineer’s separation of car and pedestrian to make safer streets, then we need to make them safer for everyone.

Continue reading

“We are an evil people, and we deserve to be punished”

It was meant to trumpet an aspirational lifestyle and showcase the very pinnacle of luxury living in one of London’s most exclusive new residential towers, where penthouses are currently on the market for over £4m. But property developer Redrow’s latest promotional video has been pulled just days after it was launched online, having been subject to an online battery of ridicule and claims that it epitomises the dystopian nightmare of London’s iniquitous property market.

The Problem Is Not The Starchitecture. The Problem Is What Gets Left Out Of The Discussion.

ALMOST AS SOON AS THE ACE HOTEL OPENED in New York City, the word spread among the cool tech kids and the young beautiful people that the Ace lobby was the place to meet and work. Blogs like This Is Going To Be BIG wrote about it, then Curbed, and soon it was in the mainstream media like the New York Times and New York magazine.** Nevertheless, years later, the cool kids still go there all day.

This contradicts a lot of what we’ve heard about architecture and design in New York for the last decade or so. During the time of the Bloomberg administration, New York City strongly and effectively promoted Starchitecture and shiny iconic towers as important parts of “dynamic, 21st-century cities.” At the same time, new Design and Construction Excellence policies focused on a specific vision of architecture that in the end excluded traditional and eclectic architects from city work, even though New York voters and residents would be surprised to hear that (and wouldn’t support that). A tour of places where the young and the hip hang out in the city shows that they like Classicism, Modernism, and a blend of the two, like the Ace. One could go further and accurately say that the iconic glass towers are the face of Global Capitalism, which becomes more and more unpopular among many New Yorkers of all ages. Contributing to that dislike are the Starchitect-designed, Manhattan mega-towers where non-resident plutocrats park flight capital in what London Mayor Boris Johnson calls “bullion pots in the sky” (aka, “iconic towers”).*

The Ace Hotel was designed by Roman and Williams, whose work ranges from eclectic places like the Ace lobby to traditional spots, like the restaurant at the Ace, just off the hotel lobby (none of Roman and Williams’ work is shiny modern). The Ace restaurant, called The Breslin, is genuinely traditional—many who go there probably think it’s an old New York restaurant, even though it was built in 2009. Like most Roman and Williams places, it has new furniture and fixtures with distressing to give them an “old” patina. It’s run by one of the hottest chefs in New York, and can genuinely be called hip.

This One’s Better Than That One

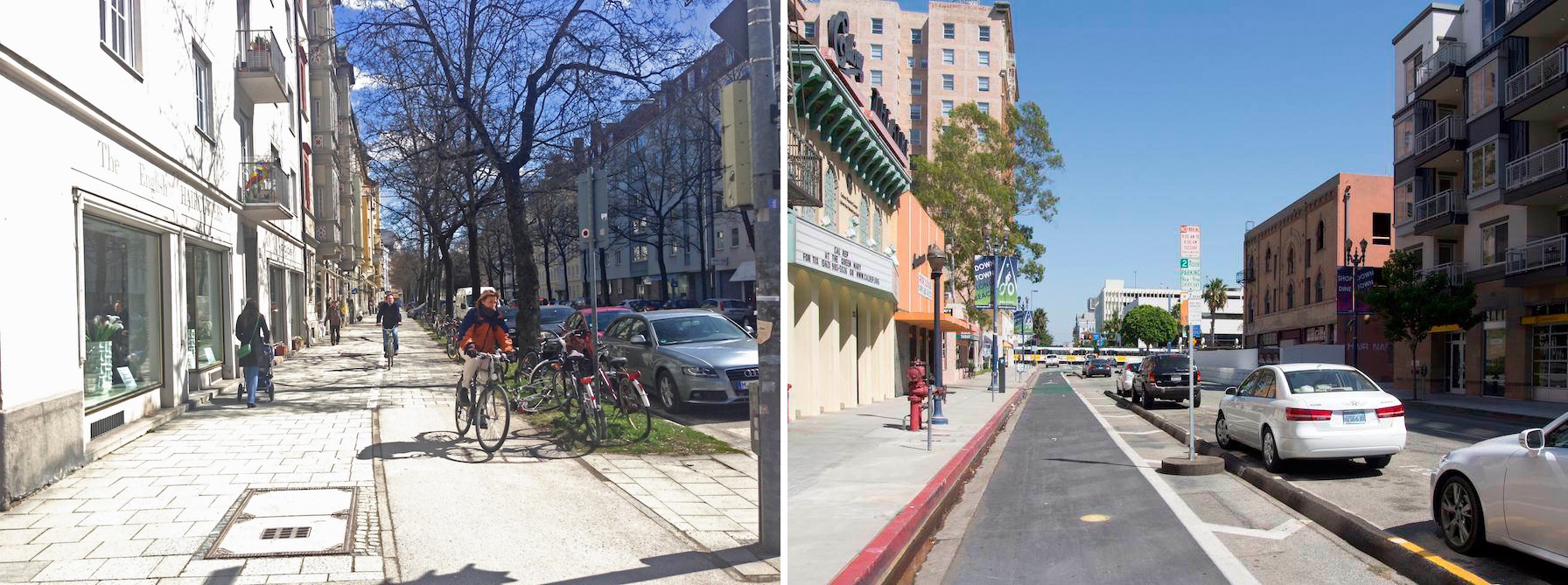

ON THE LEFT is a bike lane in Munich. On the right is what is becoming one of the most common American bike lanes, the protected lane on a one-way arterial.

The one on the left is good urban design. The one on the right is engineering, specifically traffic engineering. It’s a good evolutionary step, but as you can see, making a street where pedestrians want to walk, or where drivers want to get out of their car and walk, was not a part of the design process. It’s a suburban-style, one-way transportation corridor, now with bike lane added. It is much better than what came before—a high-speed arterial where riding a bike was dangerous and unpleasant—but as we work towards more walkability and important goals like Vision Zero, let’s agree that it’s not where we want to end up.